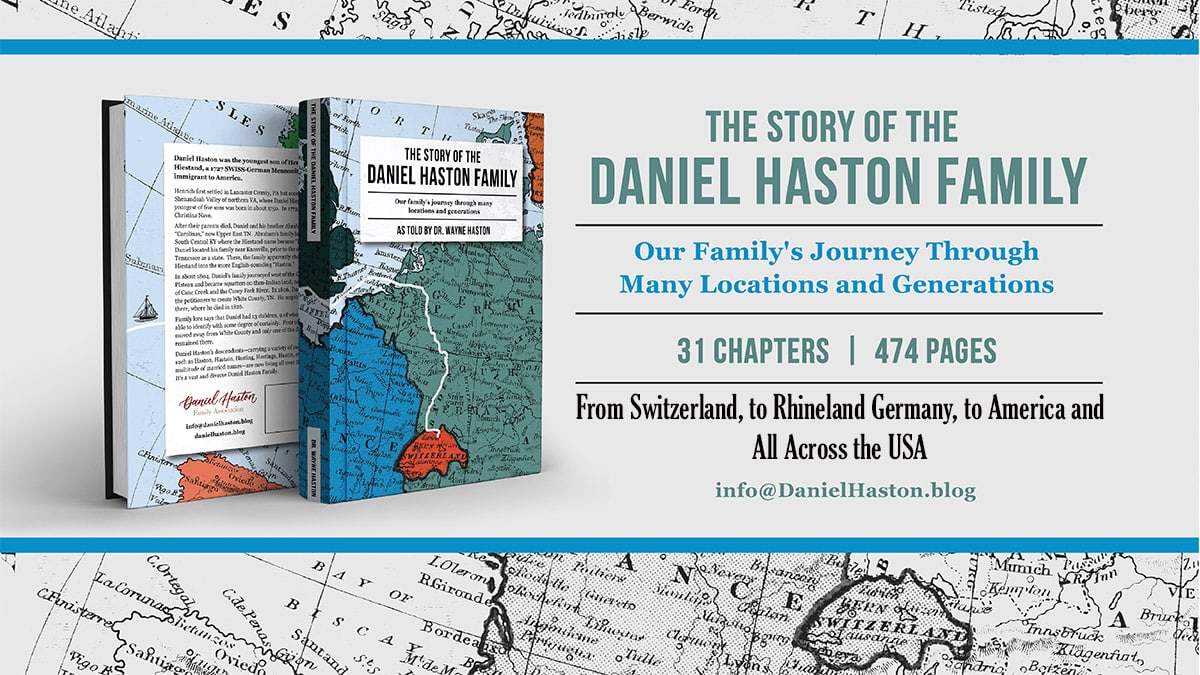

07 - Henry Hiestand - His Earliest Years in America

For Americans, an "immigrant ancestor" is an ancestor who emigrated from some other country, to come to and settle in America. Henrich (Henry) Hiestand is the immigrant ancestor for all of us who trace our lineage back to him—the first immigrant in our Hiestand line. Daniel Hiestand/Haston and his siblings were first-generation Americans, born in America as the children of their immigrant father, Henrich.

According to the Bible record of his son Peter, our Henrich (Henry) Hiestand was born on October 8, 1704.[i] Henrich’s grandson Joseph Hiestand (son of Henrich’s oldest son Jacob), stated that his “grandfather Hiestand was…a native of Germany, and emigrated to Lancaster County, PA in 1727.”[ii] This Joseph Hiestand was a nephew of our Daniel Hiestand/Haston.

[i] “Peter Hiessandt, Sr.’s Bible.”

[ii] Joseph Hiestand, quoted in John Powell, Authentic Genealogical Memorial History of Philip Powell, of Mifflin County, PA: And His Descendants and Others, Miscellaneous Items and Incidents of Interest, Volume 1. (1880 reprint; n.p., Andesite Press, 2017), 368.

If Henrich Hiestand arrived in 1727, prior to his October 8 birthday, he would have been 22 years old at the time he landed in Philadelphia. Another source says that he was single when he arrived. So, we might assume that one motivating reason for his emigration to America was to secure land to own and farm in order to build a life for himself, the wife he hoped to find, and the family he dreamed about having.

How Did Henry Pay for His Trip to America?

Many of the early immigrants to America were poor and not financially capable of paying for all of the fees at toll stops down the Rhine, the ship passages across the English Channel and Atlantic, as well as food and other necessities while they were in Holland and England. Add to all of that, the unexpected costs related to corruption and theft. Even if travelers thought they were financially prepared for the journey, often unexpected expenses impoverished them and forced them into debt. Instead of turning them away, ship captains found another way to squeeze money out of these prisoners of debt.

One: Wealthy men met these ships at the docks in Philadelphia, eager to pay the debts of passengers if they would agree to work off their debts, as indentured servants, over a period of several (usually 3 to 6) years.

Like so many other Palatine (Palatine = people from the Palatinate of Germany) emigrants, Henrich may have been forced to indenture himself to some wealthy English Pennsylvanian who paid his debt to the captain and provided room and board for him until he could “redeem” himself by a few years of servitude. But Henry appears in western Lancaster County, PA a year later among other Mennonite families, which suggests he was not in servitude.

Two: Perhaps Henrich had enough money to pay all of his travel expenses and fees, as well as enough money to survive in America until he could find a job that would pay for his living expenses until he could purchase his own farm. At age 22, that is unlikely unless he had gotten financial help from someone.

In the next article, you will learn that–for some reason–our immigrant ancestor borrowed a sizeable amount of money from a wealthy Philadelphian who arrived in Pennsylvania from the Rhineland of Germany ten years before our Henry. Caspar Wistar had only nine pennies to his name when he arrived, but within 10 years he was quite a wealthy man. Did Henry use this borrowed money to pay the expenses for his trip to America?

Hiestands Who Preceded Him to America

Just getting to America and paying for the journey was a major challenge. But for many of the immigrants, becoming established—socially and financially—was equally difficult. Some of them wandered through the streets of Philadelphia, begging for food and shelter, or a job so that they could work for their survival. No doubt, many of them succumbed to poor health that developed during the voyage, starved to death, or died of exposure to harsh weather conditions. What kind of situation did Henrich Hiestand find himself in when the ship he was on docked in Philadelphia? We do not know for sure, but….

Henrich may have had a friendly contact who had preceded him to America (relative or acquaintance from his homeland) who helped him get settled in Pennsylvania. One of the cornerstones of Mennonite life was mutual aid, especially hospitality extended to fellow Mennonites in need. “Newcomers to America could count on spending the first few weeks adjusting to their new homeland in eastern Pennsylvania at the tables of other Mennonites who were already well established.”[i]

[i] Roth, Stories: How Mennonites Came to Be. (Scottsdale, PA: Herald Press, 2006), 144.

Often Palatine immigrants were met at the port in Philadelphia by relatives or friends who had already traversed the Atlantic and established homes and sources of income here. These contacts from “back home” generally provided temporary food and shelter and assistance in getting newly arrived immigrant loved ones settled in and established on their own. But were there other Hiestand family members or friends of Henrich or his European family who could have met him when he arrived in America or provided him with temporary shelter and assistance?

We do know that our Henrich Hiestand was not the first Hiestand to come to America. There were at least two or three Hiestands and one daughter of a Hiestand who arrived some years before him. And there were several other earlier emigrant families to Pennsylvania from the Rhineland, even Ibersheim and its surrounding villages, that undoubtedly were acquainted with Henrich’s family back home.

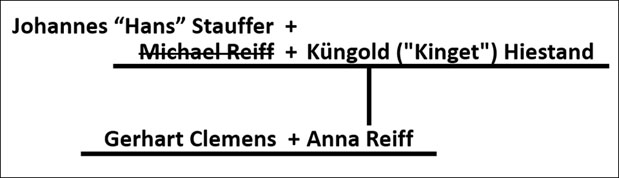

Küngold (“Kinget”) Hiestand Stauffer and her husband Hans Stauffer landed in America more than 15 years ahead of Henrich. Kinget (born January 1658 in Richterswil, Switzerland) married Michael Reiff, also of Richterswil. Because of persecution, this young Anabaptist couple moved from Richterswil to the Palatinate in Germany, probably Ibersheim first and then the nearby-village of Mettenheim (or Metterheim), where Michael Reiff died. One child, Anna (Anneli) Reiff, was born to Michael and Kinget (Küngold) Hiestand Reiff before Michael died.

After Michael Reiff’s death, Kinget Hiestand Reiff married Johannes “Hans” Stauffer, a 40-year-old bachelor,[i] in 1685 in Alsheim, Germany. Ibersheim, Mettenheim, and Alsheim are all within a very few miles (or km) of each other, north of Worms, Germany on the west side of the Rhine River. Hans and Kinget Hiestand Reiff Stauffer emigrated to America in 1710.

[i]James W. Lowry, Documents of Brotherly Love, Volume I. (Millersburg, OH: Ohio Amish Library, 2007), 403.

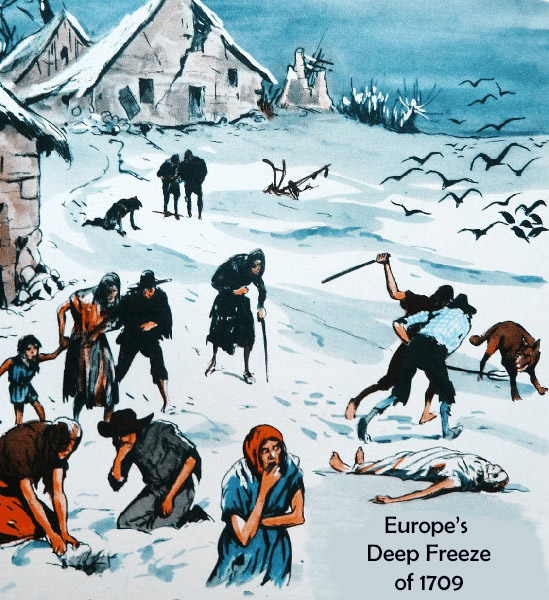

Kinget’s daughter and son-in-law, Anna and Gerhart Clemens, preceded Hans and Kinget to America by a year or so. On January 10, 1709, the swift-flowing Rhine closed due to ice and remained closed for five weeks. The 1708-1709 winter was the coldest winter in Europe in the past 500 years–Europe’s Deep Freeze of 1709. And the War of Spanish Succession (1702-1714) was wreaking havoc on the Palatinate—life there was again becoming intolerable.

And coincidentally, Queen Anne of England was circulating information throughout the Rhine Valley offering free transport to Palatines who would come to England to be sent to America as settlers of her expansive English colony. In about March of 1709, Gerhart Clemens sold his possessions to his father and brother, preparing to travel to America. Gerhart’s notebook indicates that by October 1709 he was in Pennsylvania.

Gerhart and Anna Reist (Hiestand) Clemens first settled in the Skippack community (30 miles northwest of Philadelphia) in what is now Montgomery County, PA. They later moved to Salford Township. Wherever they went, it appears they were prominent members of the community.

On April 15, 1726 Abraham Hiestand sold a cow to Gerhart (Gerhard) Clemens in Lower Salford Township of what is now Montgomery County, PA (previously part of Philadelphia County). From the account book of Gerhart Clemens: “I bought a cow of Abraham Heistand, April 15, 1726, for L3 ts.”[i] How does he fit into the European Hiestand family? We do not know–but he was a Hiestand and, no doubt, a relative of our Henry.

[i] Clemens, 5.

Prior to 1727, several ex-Ibersheim families had already settled in Pennsylvania, even as far into the wilderness as what became Lancaster County. Such families as the Brubakers and Neffs were closely associated with the Hiestands in Ibersheim and other villages near there. Henrich Hiestand’s extended family was interwoven with most of these families by marriage. No doubt these families would have welcomed Henrich to join them as a farmhand until he could earn enough money to purchase his own farm.

When Henry Hiestand arrived in Pennsylvania, there were friends and family members who probably took him in and allowed him time to transition to an independent life in America.

April 1728 - Mennonite Naturalizations

Beginning in September 1717, Palatine immigrants were required to declare their loyalty to the King of England soon after landing in Philadelphia. Prior to that time, they were still officially subjects of the Emperor of Germany even though they were living in Pennsylvania. As aliens they were deprived of some very important rights enjoyed by English-born Pennsylvanians. Although they could purchase land, they were not allowed to sell land to others nor were their children allowed to inherit their land. It doesn’t seem fair does it?

Attempts by Pennsylvania Mennonite leaders to become naturalized as British citzens in Pennsylvania were continually defeated or tabled in the Pennsylvania Assembly, largely because the Mennonites would not agree to make an “oath” of allegiance to the British Crown. Making oaths violated their Christian convictions. But finally the Pennsylvania Assembly agreed to allow Mennonites to make “declarations of allegiance” to the British Crown without calling them oaths.

On April 1 and 2, 1728, two Chester County justices traveled to the home of Martin Mylin near Conestoga Creek south of Lancaster, PA. Mylin’s home was about 11 miles southeast of the tract that Henry Heestant had surveyed seven years later. At that time, approximately 200 Mennonites formalized their declarations of allegiance:

“Wee … do Sincerely and Solemnly Declare before God and the Word that wee will be … faithful to King George the Second.”

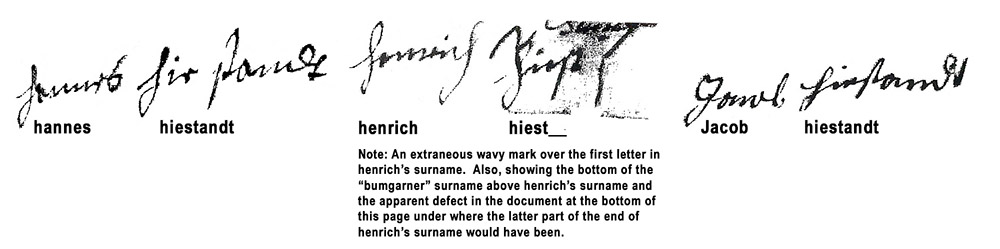

The names of hannes (John) Hiestandt, henrich hiest, and jacob hiestandt were among the signatures added to the document of declarations of loyalty to the British Crown.[i] There was some kind of defect in the document near the end of Henrich’s surname, thus it appears as “hiest_.”

[i] “Declarations for Naturalization Signed by Mennonites of Chester County, PA.” (On file: Archives of Chester County, PA, April 1, 1728).

After some further stalling by the Assembly, on March 29, 1735 “An Act for the Better Enabling Divers Inhabitants of the Province of Pennsylvania to Hold Lands and to Invest Them with the Privileges of Natural-Born Subjects of the Said Province” was passed.[i] But, two factors limited the extent of the Mennonites’ benefit from the bill. First, the bill only provided citizenship for immigrants who arrived in Pennsylvania between 1700 and 1718. That eliminated about one-half of the signers, no doubt including Henrich Hiestand. Second, when the German speaking pacifist signers learned the true nature of the English language “declaration” they had signed, most of them balked.

[i] “Chapter 339″ of the Laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Volume I. (Philadelphia: John Bioren, 1810), 283.

The signers discovered that they had unwittingly agreed to take up arms to defend the Crown. Nearly two decades later, the 1747 Act of Parliament finally provided Mennonites the freedoms they had desired for decades without the obligations that offended their consciences.[i] When the Naturalization Bill was finally passed on February 14 of the 1729/30 meeting of the Assembly, most of the signers were not naturalized at that time, including some of the more prominent Mennonite leaders.[ii]

[i] Garber, 551-560.

[ii] Garber, 557.

What about our Henrich Hiestand? Was he ever officially naturalized as a subject of the British Crown, if not in 1728? If so, when and where? Well, we know he voted in an 1855 election in Virginia which supposedly required British citizenship. And that’s all we know about his naturalization.

In the next article, you will see exactly where Henry Haston settled in Lancaster County, PA before moving south to his final settlement in Virginia…and much more.

If you enjoyed this article, please share it with others who might be interested.