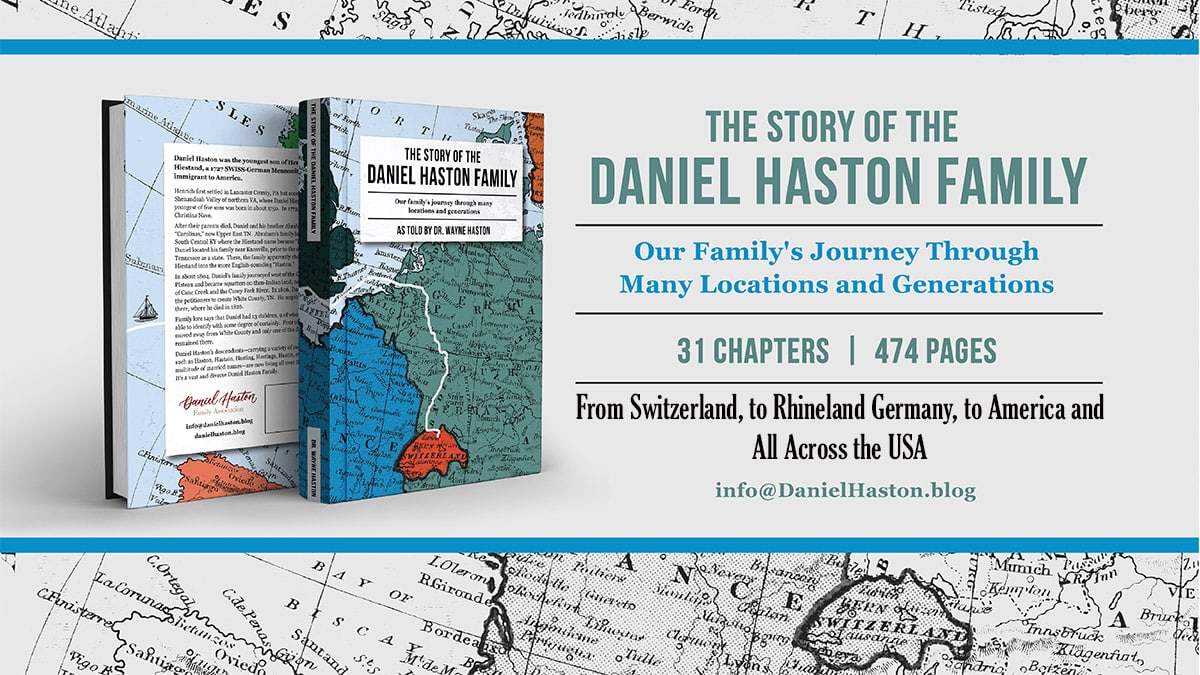

10 - Indian Attacks Around Our Hiestands in Pennsylvania and Virginia

As a kid, cowboys and Indians was just a fun game we played. And the battles between Indians and American pioneers was just something we enjoyed watching on our old black and white televisions. But when you read the real stories that your ancestors lived, it makes you feel—to a tiny degree–the fears that haunted them day and night.

Think about this: If our Daniel Haston, or his son or daughter that you descend from, had died in one of those Indian attacks, you (and your children and grandchildren, etc.) would never have been born.

The constant threat of warfare along the Rhine River in Germany was probably a contributing factor to Henrich Hiestand leaving home in about 1727. His homeland had a long history as a battlefield for warring European nations. I wonder if Henrich was aware that beyond the coasts of America, most every settlement was a potential battlefield, with Native Americans fighting white settlers to protect their long-held hunting grounds and village sites.

Indian Troubles in Pennsylvania

Although William Penn had tried to keep peace with the Native Americans, as he passed off the scene and European settlers kept expanding inland, hostilities between the natives and the white intruders were virtually impossible to suppress.

As it turned out, just about the time our Henry Hiestand settled in western Lancaster County, just east of the Susquehanna River, animosity between Indians and colonists turned deadly. Henry’s 226 acres in Hempfield Township of Lancaster County was right on the edge of the frontier where settlers were not safe.

The Quakers who dominated Philadelphia and controlled all of Pennsylvania politically were pacifists. They refused to take action to protect their citizens in western Lancaster County. North of where Henry Hiestand lived, in northwestern Lancaster County and Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, most of the colonists were Scots-Irish, not Mennonites, Quakers, or other Englishmen. The Scots-Irish had a long history of fighting for their survival back in Europe. Unwilling to turn the other cheek when attacked, they retaliated and the hostilities escalated.

At that same time, white settlers in Northern Virginia were experiencing peaceful relations with the Native Americans–in some cases living near each other as good neighbors should. Whether or not our Henry Hiestand moved to Virginia to flee the war zone of western Lancaster, I do not know. But ten years later, similar–even more challenging–Indian troubles followed him.

French and Indian War in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia - 1754-1763

In November 1753, the governor of Virginia dispatched George Washington, then a 22-year-old lieutenant colonial in the Virginia militia, to the area where the Monongahela and Alleghany rivers form the Ohio River. Forty men were assigned to accompany the young Lieutenant Colonel Washington. His mission was to stop the French and Indians from building forts in the backcountry of Pennsylvania and Virginia and claiming that territory for France. As they approached their destination, Washington’s troops were forced to retreat and soon had to surrender at a tiny, hurriedly constructed fortress known as Fort Necessity.[i]

[i] Matthew C. Ward, Breaking the Backcountry: The Seven Years’ War in Virginia and Pennsylvania, 1754-1765. (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2003), 32-35.

In 1754, something ominous occurred in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia—the Indians in and around that area suddenly disappeared and crossed the Alleghany Mountains to the west. In the previous year, emissaries from Indian tribes west of the Alleghanies had visited the valley Indians and communicated a scheme that would soon disrupt the peaceful relations white settlers had enjoyed with Indians for more than 20 years. Suspicions of a brewing French and Indian storm soon became a reality.[i]

[i] Kercheval, 49.

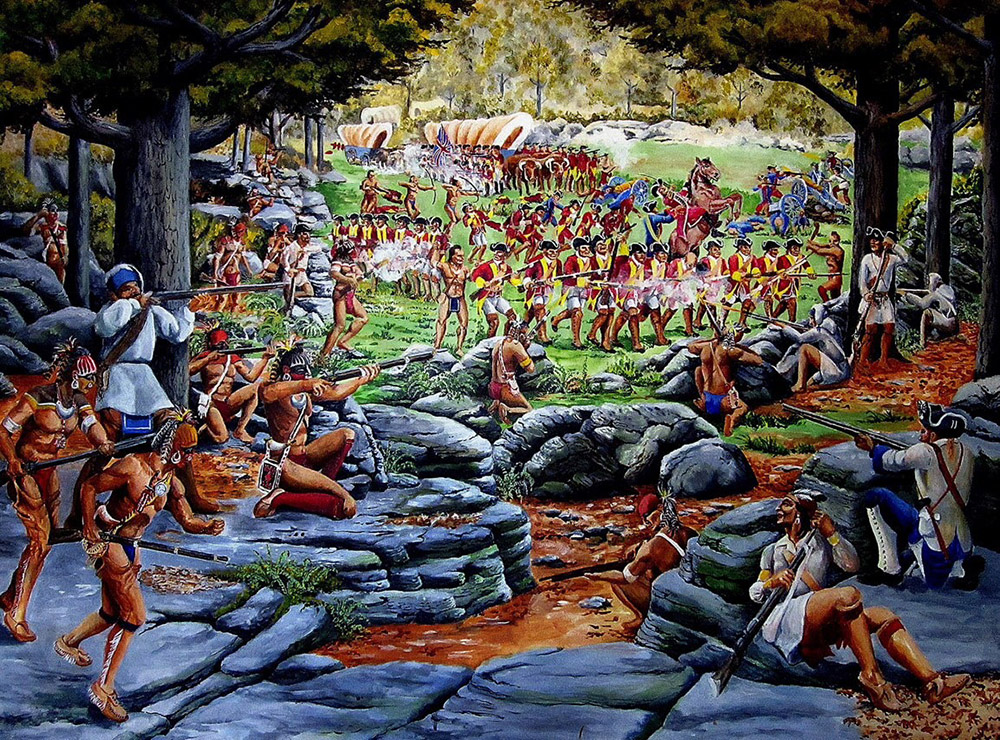

The following year, British authorities sent Major General Edward Braddock and 3,000 troops to the head of the Ohio River to do what Washington and his militiamen were not able to do. Braddock had a lot of experience and success in European warfare but was ignorant of fighting in an American wilderness. And Braddock was an arrogant and bull-headed man who would not listen to colonist soldiers like Washington or his Indian allies who tried to advise him of the errors in his plan and approach. As a result, the July 1755 “expedition suffered one of the most decisive routs in British military history”[i] and Braddock was killed in battle.

[i] Ward, 36.

With the defeat of Braddock, the French-Indian coalition was emboldened and panic broke out in western Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia as the backcountry lay exposed to Indian attacks. France and England officially declared war the next year, which we know of as the French and Indian War but is more commonly known elsewhere as the Seven Years War (1756-1763).

One of the key distinctives of Mennonite faith and practice was, and still is, pacifism—refusal to go to war. For several generations, Henry Hiestand’s ancestors had been ostracized and persecuted for refusing to go to war, even defensive wars. On September 2, 1755, less than two months after Braddock’s defeat at the Battle of the Monongahela and while settlers in western Virginia were living in fear of Indian invasions, our Henry Hiestand was fined for not participating in a militia muster. At a court-martial in Frederick County, it was ordered by the “Rt. Honble. Thomas Lord Fairfax County Lieutenant” that “Henry Histand of the foot Company Commanded by Capt. William Bethel be fined ten shillings or one Hundred ll. of Tobo. [tobacco] for Absenting himself from one* Private muster within twelve months last past.”[i]

[i] Richard K. MacMaster, Samuel L. Horst, and Robert F. Ulle, Conscience in Crisis. (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1979), 157.

By early 1758 large war parties of Indians roamed freely in the Shenandoah Valley, capturing and killing white settlers. Klaus Wust described the plight of Massanutten families poignantly in these words: “During March and April 1758, the settlements in the South Branch [Shenandoah River – where our Hiestands lived] valley were annihilated.” John Stone (probably the son of Ludwick Stein/Stone) and his family were massacred at their home in the heart of the Massanutten Settlement. The Abraham Brubaker family who lived near the Stones was spared of a similar fate because Mrs. Brubaker had spotted the Indians, two miles away, on the previous evening and was prepared to flee at any additional sign of danger.[i] In the Hawksbill community, a couple or miles or so from the Hiestands, Jacob Holtiman, his wife and children were killed and a Grandstaf family was taken prisoners.[ii]

[i] Strickler, Massanutten Settled by the Pennsylvania Pilgrim, 1726, 85-86.

[ii] Wayland, A History of Shenandoah County, Virginia, 68.

Shenandoah Valley Mennonites Flee Back to Pennsylvania

“Within a few weeks, most German neighborhoods in northern Virginia were abandoned. Many fled east of the Blue Ridge, others moved with hastily gathered belongings whence they had come years ago—to eastern Pennsylvania.” “For several weeks, Indians struck out of the Massanutten Mountains at whatever sign of life they could perceive.”[i]

[i] Wust, 63.

While in refuge with friends and family back in Lancaster County, four Mennonite leaders (Martin Kauffman, Jacob Burner, Daniel Stauffer, and Samuel Boehm who was Abraham Hiestand’s future father-in-law) from the Massanutten Settlement wrote a letter dated September 7, 1758* to fellow Mennonites in Holland, asking for financial assistance.

We were 39 Mennonite families living in Virginia. One family was murdered and the remaining of us and many other families were obliged to flee for our lives, leaving all and going empty handed. Last May the Indians murdered over 50 persons and more than 200 families were driven away homeless… We come therefore with a prayer to you brethren and fellows in the faith for help, by way of charitable aid.[i]

[i] Harry Anthony Brunk, History of Mennonites in Virginia, 1727-1900. (1959; reprinted, Harrisonburg, VA: Vision Publishers, 2012), 25.

The Dutch Mennonites responded with a gift of 50 pounds English sterling.

No doubt the Hiestand family was one of the 39 families mentioned in the letter. But apparently, the Massanutten refuges did not remain away from their Virginia homes for long.

First hesitantly, then almost in full numbers, the people returned to their homes and fields. From the latter part of 1758 until 1761, the German settlements in the lower Valley and in the Southwest were quiet. Life was almost normal again. Houses and barns gone up in flames had to be rebuilt. Many of the homes constructed now had an added feature: the vaulted cellar which would serve as a fort of last resort for family and neighbors.[i]

[i] Wust, 64.

Our Daniel Hiestand/Haston would have eight years old when his family temporarily returned to Pennsylvania for refuge. This and other memories of that time would have been with him for the rest of his life.

Massacre of the Hiestand's Neighbors

Rev. John Rhoads, Wife, and Six Children

The French and Indian War officially ended in 1763, but one more major Indian attack occurred in the valley a year after the Treaty of Paris that ended that war. It was such a savage event that it still lingers in the minds of some Massanutten area people today.

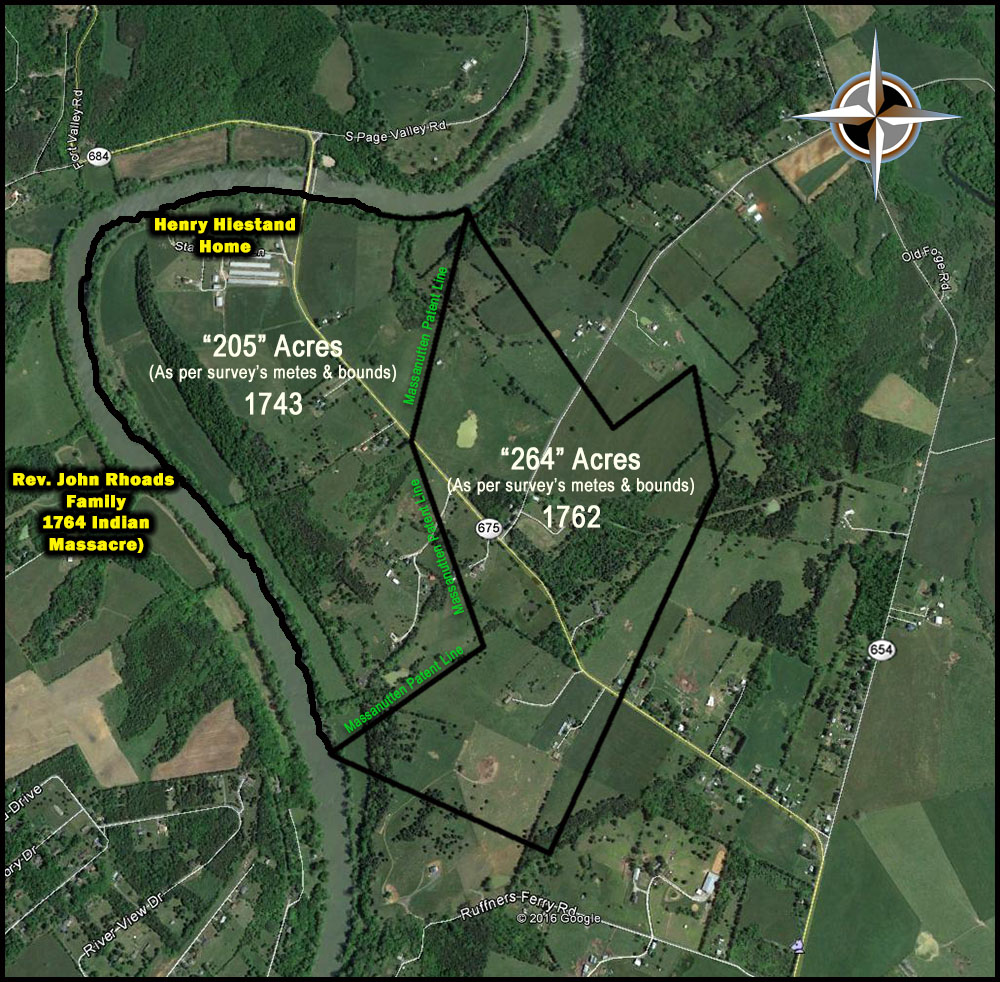

Late in August of 1764, “a party of eight Indians and a worthless villain of a white man crossed Powell’s Fort Mountain, to the South Fork of the Shenandoah.”[i] They probably travelled through or very near Henry and Abraham’s properties in Fort Valley. The Indians murdered Rev. John Roads, his wife, and three of his sons at or near the homesite. One of the boys tried to cross the river to escape, but the pursuers caught the boy and killed him in the river. Into the 1800s, or perhaps even later, that crossing was known as “Bloody Ford.” The Roads family lived just across and up the river from the Hiestand family, and it is very possible that this young son of John Roads was headed to the Hiestand home for protection and help. The oldest daughter, Elizabeth, ran to the barn with her baby sister. When the Indians set the barn on fire, Elizabeth escaped through a hole in the barn, ran through a tall hemp field with the baby, and crossed the river to safety at a neighbor’s house. The Indians then set fire to all the other buildings and took two sons and two daughters as prisoners. As they reversed their course and crossed Powell’s Fort Valley the Indians killed one of the boys, a sickly lad, as well as the two girls who refused to go with them. The other boy, Michael, remained in captivity for three years before returning home.[ii] Michael claimed that he personally watched some French men pay these Indians per scalp for his family’s scalps.[iii] Later, Elizabeth married Jacob Gochenour, son of the senior Jacob Gochenour who was the brother of Joseph Gochenour, Henry Hiestand’s friend and neighbor back in Lancaster County—possibly Henry’s first cousin.

[i] Kercheval, 101.

[ii] Kercheval, 101-102.

[iii] Wayland, A History of Shenandoah County, Virginia, 73.

Our Daniel Hiestand/Haston would have been about 14 years old at the time and would have seen the fires across the river, heard the story firsthand from Elizabeth, and perhaps even witnessed the mutilated bodies.

More Indian Threats Later in Tennessee

Later, when Daniel Haston moved to Western Carolina (now East Tennessee) his family faced similar threats for several years. But more about that later.

If you enjoyed this article, please share it with others who might be interested.