One of the Most Heroic Units in the Mexican War

I have no photo of him. I have no details of his specific activities during his year of service in the Mexican War. He was only a private. He was only a volunteer, not a member of the Regular Army. He only served 12 months. But I do know that he was a member of one of the most heroic units that fought in the Mexican War. Some of their exploits are hard to imagine, including some feats that definitely contributed to the USA’s victory in the war.

War With Mexico Was Coming

Texas won its independence from Mexico in 1836. But Mexico had hopes of recapturing its former northern state. Texas was annexed by the United States on December 29, 1845, which didn’t sit well with Mexico’s leaders. Mexico and Texas continually disputed the southern border of Texas–Texans claiming the Rio Grande River as the border. Mexico was only willing to admit to the Nueces River. So a lot of territory claimed by Texas and the US was disputed territory.

Many Americans of the first half of the 1800s were believers in Manifest Destiny–the idea that God had destined the United States to expand across North America. In order to accomplish that, Mexican’s land holdings in the southwest and west coast would have to be purchased or conquered. In the early 1840s, tensions were building in both countries.

1st Missouri Regiment of Mounted Volunteers

In order to engage Mexico in a war (Mexican War of 1846-1848), when President John K. Polk called for volunteers to supplement the United States’ regular army in early 1846, Missourians volunteered quickly. Some men were inspired by the challenge of the adventure, others probably hoped for military bounty land at the end of their service, some no doubt were staunch believers in Manifest Destiny. But many were haunted by the “ghost of Okeechobee.” In a previous war with Seminole Indians in Florida, many of the Missouri soldiers fled in the heat of the Battle of Okeechobee. For nearly 10 years, Missouri men were viewed as cowards. A war with Mexico gave them an opportunity to erase that haunting stereotype and reclaim manhood for Missourians.

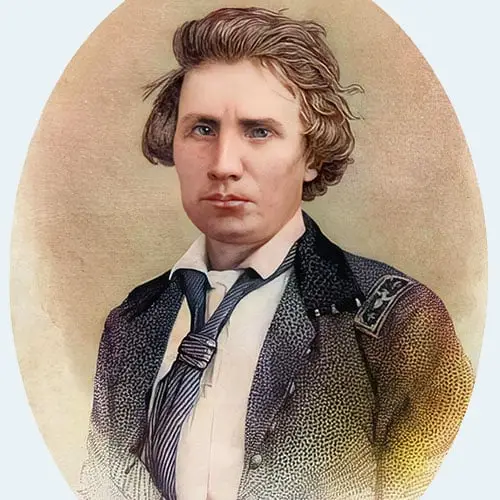

Alexander William Doniphan (July 9, 1808 – August 8, 1887) was a 19th-century American attorney, soldier, and politician from Missouri who is generally best known today as the man who prevented the summary execution of Joseph Smith, founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, at the close of the 1838 Mormon War in that state. -Wikipedia

Colonel Alexander Doniphan is also famously known as an outstanding leader of United States military forces during the Mexican War. He recruited a regiment of Missouri volunteers and led them to victory after victory against imposing odds.

Missouri’s Governor John Edwards called upon Alexander Doniphan, a civilian lawyer, and militia colonel, to raise a regiment of hundreds of volunteers from Missouri, which he gladly agreed to do. Doniphan was well-known and well-liked across Missouri, from his town of Liberty all the way to St. Louis. Although he had no real military training and experience, other than militia participation, he was a good learner and a great leader.

Doniphan’s regiment was called the 1st Regiment of Missouri Mounted Volunteers.

Company G from Howard County, MO

Company G of the 1st Regiment of Missouri Mounted Volunteers was from Howard County, MO where Daniel Haston’s son Jesse settled in about 1818.

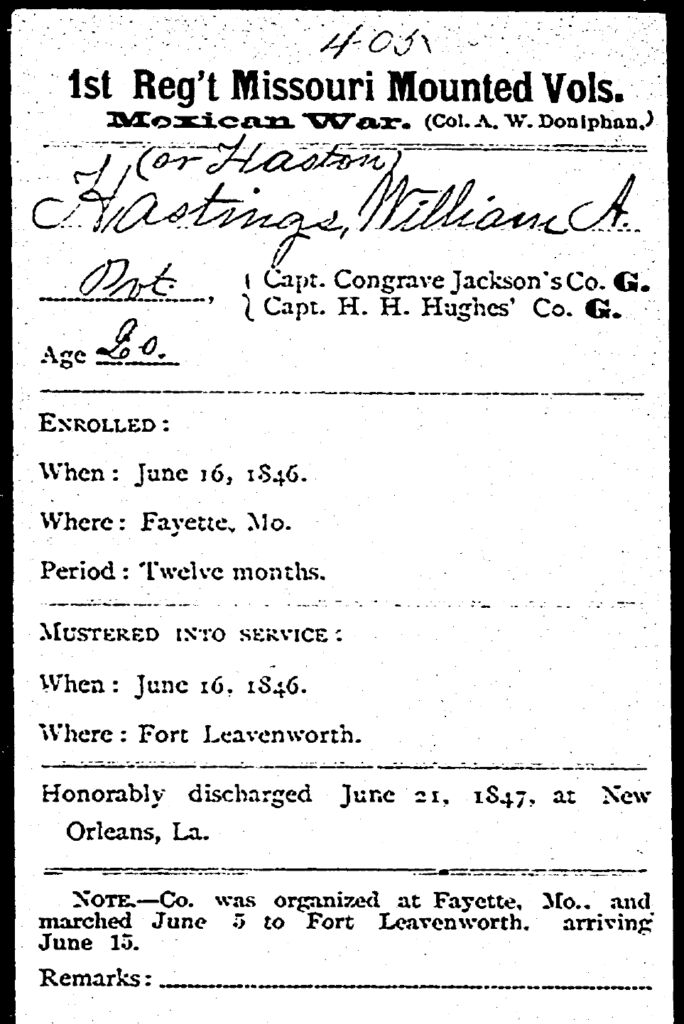

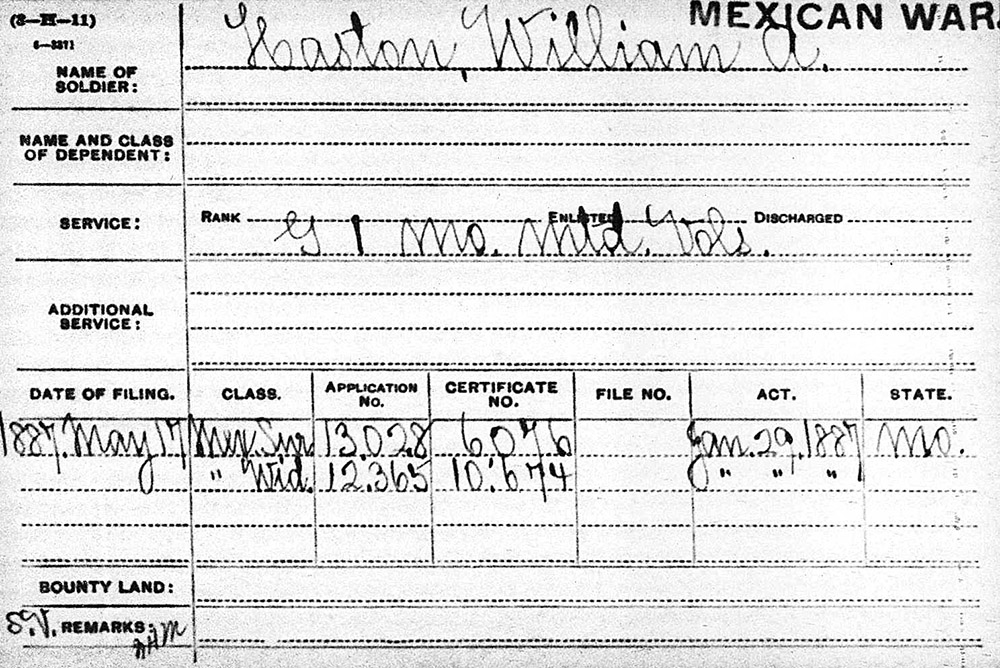

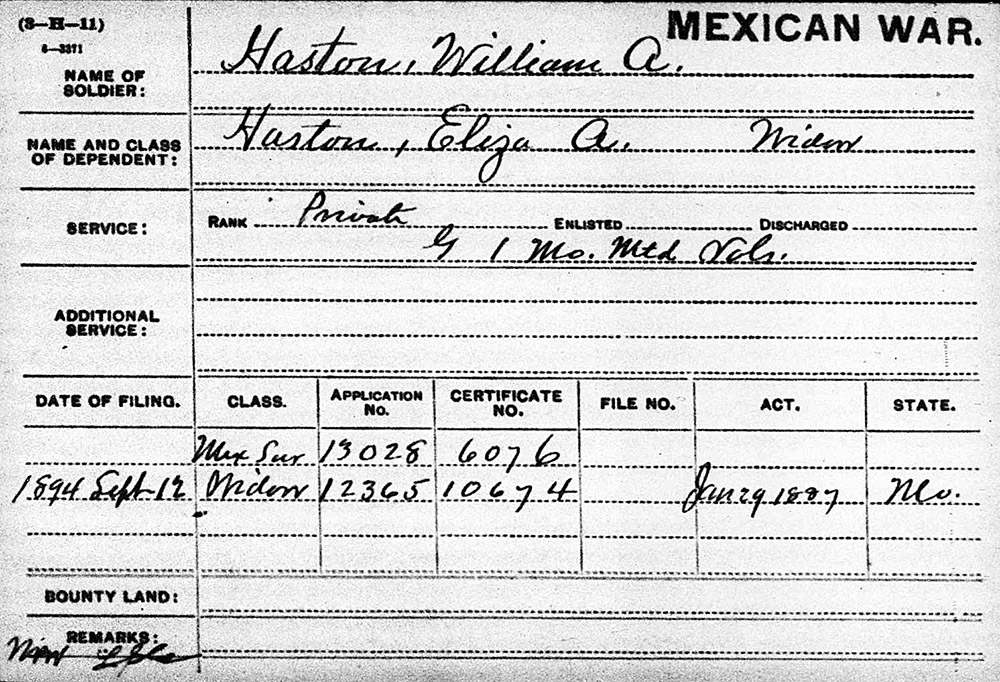

Captain Congrave Jackson, from Howard County, was the commander for Company G. Twenty-two-year-old William Asbury Haston gathered with Captain Jackson’s recruits in Fayette, MO and then travelled with them to Fort Leavenworth where they were officially mustered into service on June 16, 1846, and trained for three weeks. William A. Haston and the other volunteers enrolled for a period of 12 months–not a long time to accomplished what they were assigned to get done.

Col. Doniphan & Exploits of Missouri Volunteers

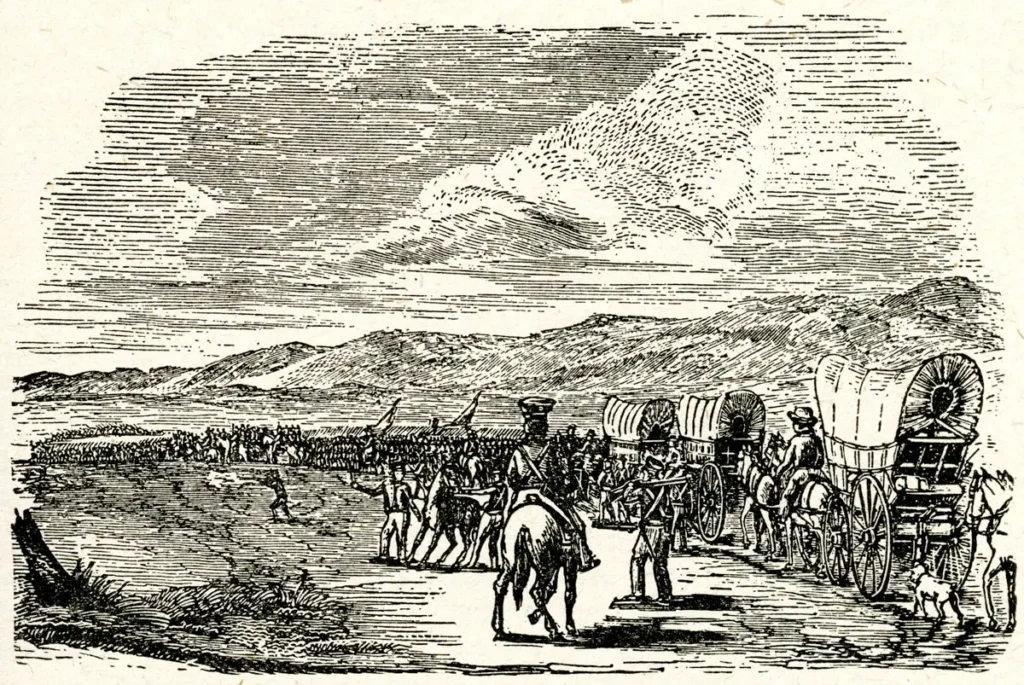

The story is too long to tell here, but here are some of the exploits of Doniphan’s Missouri volunteers. Now, remember, with some exceptions, these were volunteers–farmers, lawyers, merchants, etc. They only had a few weeks of military training at Fort Leavenworth and no (zero!) experience in battle.

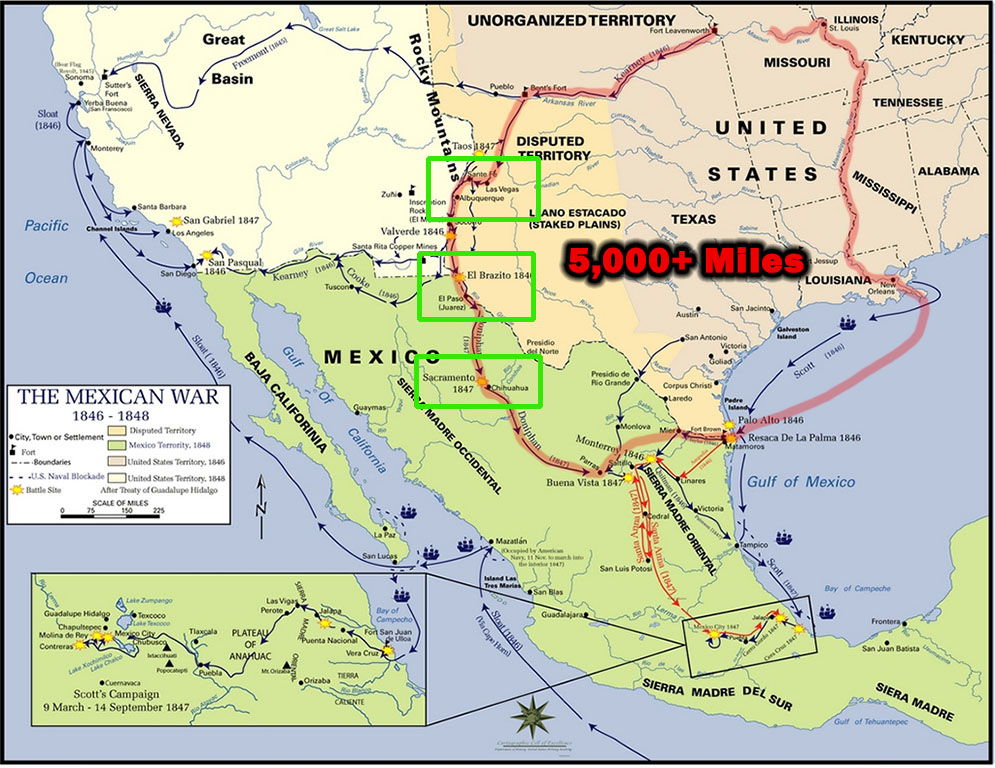

They travelled 600 miles from Fort Leavenworth down the Santa Fe Trail to Santa Fe, New Mexico, across punishing terrain (deserts and rocky hills), without adequate water or food much of the time.

In spite of a sizeable Mexican army that threatened to defend the town at all costs, Doniphan’s volunteers captured (and held) Santa Fe (New Mexico) from the Mexican military without firing a shot or shedding blood.

Colonel Doniphan, with help from others, negotiated some treaties with Indian tribes around Santa Fe, treaties that eventually took hold.

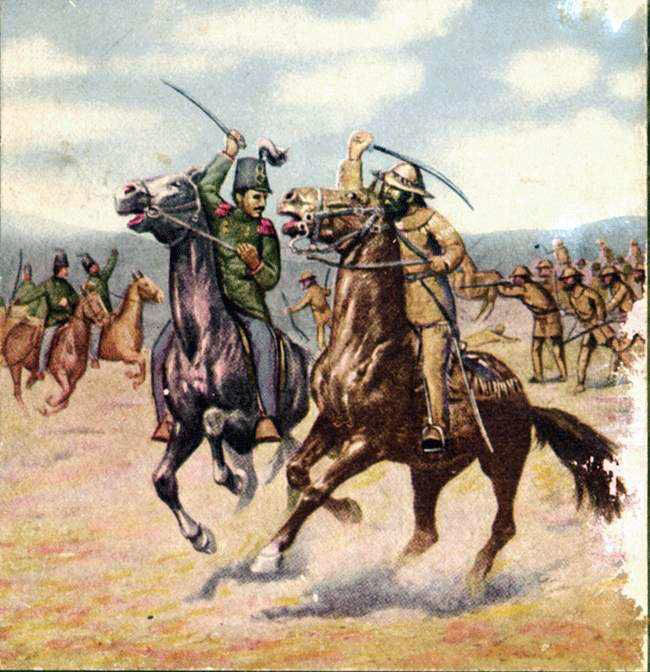

Battle of El Brazito, Near El Paso

“On Christmas day (1846), at a spot called Brazito, when the regiment after its usual march, had picketed their horses, and were gathering fuel, the advance guard reported the rapid approach of the enemy in large force. Line was formed on foot, when a black flag was received with an insolent demand. Colonel Doniphan restrained his men from shooting the bearer down. The enemy’s line, nearly half cavalry, and including a howitzer, opened fire at four hundred yards, and still advanced, and had fired three rounds, before fire was returned within effective range. Victory seems to have been decided by a charge of Captain Reid with twenty cavalry which he had managed to mount, and another charge by a dismounted company which captured the howitzer. The enemy fled, with loss of forty-three killed and one hundred and fifty wounded; our loss seven wounded, who all recovered. The enemy were about twelve hundred strong; five hundred cavalry, the rest infantry, including several hundred El Paso militia; our force was five hundred.” –Lieutenant Colonel Philip St. George Cooke

Two days later, the Missouri volunteers marched into El Paso unopposed. There they seized five tons of powder, 500 arms, 400 lances and four pieces of artillery.

Again, they crossed hundreds of miles of desert lands under some extreme conditions–lack of water, lack of decent food, sandstorms, and threats from Apache Indians.

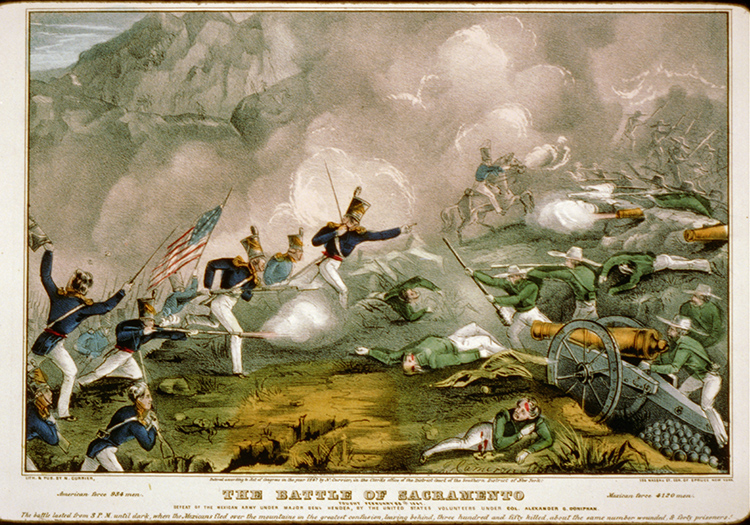

Battle of Sacramento River

The Battle of the Sacramento River took place on February 28, 1847 during the Mexican–American War. About twenty-five miles north of Chihuahua, Mexico at the river Sacramento, American forces numbering less than 1,000 men defeated a superior Mexican army of 3,000 or more which led to the occupation of Chihuahua, one of the largest cities in Mexico at that time.

Only a few of the American volunteers were killed or wounded. But when the smoke cleared, bodies of hundreds of Mexican soldiers were scattered across the battlefield, held as prisoners by the Americans, or had fled into mountains or across the deserts.

Before returning to the United States, they had marched more than 3,500 miles, one of the longest marches in military history. They had defeated three superior-size Mexican armies and conquered three Mexican cities–all in ONE year.

Including the return steamboat trip from New Orleans to home in Missouri, they traveled more than 5,000 miles.

William A. Haston's Rewards for Mexican War Service

When the Missourians returned home in the summer of 1847, they were greeted and treated as heroes–in New Orleans, St. Louis, all along the way, and back home. William’s father, Jesse Haston, was a member of the committee that organized a major celebration for the victorious men from Howard County, MO. They had erased the Okeechobee stain and Missourian men were no longer viewed as cowards. They had protected Texas from being retaken by Mexico. And they had helped fulfill the dreams of Manifest Destiny, by expanding American land in the Southwest. Those were internalized rewards they probably enjoyed the rest of their lives.

On the authority of the ScripWarrant Act of 1847, William A. Haston was granted a military land warrant for 156.62 acres in Schuyler County, MO. He sold the patent to John C. George. Forty years after his service in the Mexican War, he received a pension for his service. His pension was transferred to his widow when he died.

Doniphan’s Missouri Marksmen and the Mexican-American War

If you enjoyed this article, please share it with others who might be interested.