21 - Daniel Haston Voted in Favor of the State of Franklin

So, our Daniel was a "Franklinite"

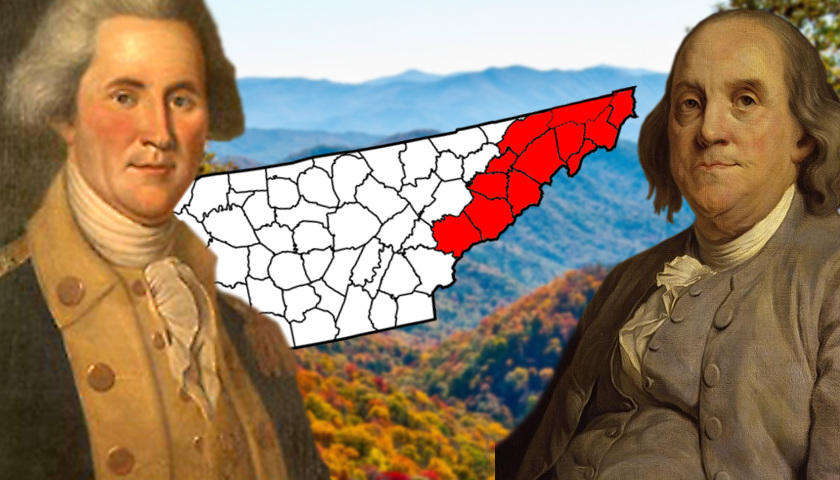

The yellow county – Washington County – is where Abraham Hiestand lived for a few years. Although there is no (to my knowledge) evidence for Daniel Haston’s specific whereabouts in the county, apparently he also lived there for a few years. Both of them moved on after staying in the Washington County area for about a decade.

Before moving to his final home westward across the Cumberland Mountain into middle Tennessee, Daniel lived approximately twenty years in what we now know as East Tennessee. About ten of the first of those years were probably spent in or around Washington County (where Jonesborough was the county seat) and the next ten or so years in Knox County, near Knoxville. Abraham Hiestand, his family of dependents, and his adult children remained in east Tennessee until they moved to Kentucky in or about 1798. Abraham lived in at least two locations in east Tennessee, but we have no record of Abraham ever living in Knoxville or Knox County (although he may been jailed there at one point).

When Abraham and Daniel left the Shenandoah Valley, like many others before and behind them, they were “headed for the Carolinas”—ultimately western North Carolina, no doubt. Because of the Land Grab Act of 1783, there was plenty of good-but-cheap land west of North Carolina’s Appalachian mountains, but the act had a narrow window of time, from October 20 through May 25, 1784.[i] When the “office was opened at Hillsboro, October 20, 1783…the ‘vast crowd’ of people assembled there was so disorderly that the office had to be closed until October 23.”[ii] “During a seven-month period in [1783 and] 1784, the land office sold almost 4,000,000 acres at five dollars per hundred acres.”[iii] The North Carolina Assembly passed this act even though much of this land was “still in the possession of Native Americans.”[iv] The act violated all existing Indian treaties that were in effect to protect Indians living or hunting in the western wilderness of North Carolina. And, in the end, it was no surprise that three million of those acres “ended up in the names of North Carolina legislators or their business partners.”[v] So most commoners missed out on grabbing lots of good-land-cheap.

[i] Jonathan M. Atkins, “The Southwest Territory, 1790-1796,” in History of Washington County Tennessee, eds. Joyce and W. Eugene Cox (Jonesborough, TN: Washington County Historical Association, 2001), 75.

[ii] Albert Lincoln Bramlett, “North Carolina’s Western Lands.” (PhD dissertation, North Carolina University, 1928), 90.

[iii] Dave Foster, Franklin: The Stillborn State and the Sevier/Tipton Political Feud. (Johnson City, TN: The Overmountain Press, 1994), 2.

[iv] Atkins, 99.

[v] Atkins, 75.

Land may have been cheap and relatively plentiful in western Carolina, but trans-Appalachian living conditions were much more primitive and dangerous than back home in the northern neck of Virginia. Except for some areas damaged from fires caused by lightning, the terrain was almost entirely covered with trees. And the land was “almost impenetrable, even the barer spots were full of impediments such as briars and brush.”[i] Most of the few roads that did exist west of the mountains were little more than swaths hacked out through a wilderness following old Buffalo trails (“traces”) and Indian war paths. Farm fields required clearing of rugged virgin forests. Courts were inadequate to handle the demands of frontier justice. Schools were almost non-existent. “Danger lurked at every turn. The forest teemed with wolves, panthers, bears, rattlesnakes, and copper heads.”[ii] And Indian raids on white settlements and lone cabins were a constant threat and frequent reality.

[i] Watauga Association of Genealogists, History of Washington County Tennessee, 1988. (Johnson City, TN: Watauga Association of Genealogists, 1988), 8. Note: 1988 book, not the 2001 book.

[ii] Watauga Association of Genealogists, 8.

The brave denizens who lived on the wilderness side of the Appalachian Mountains were taxed by North Carolina at the same rate as wealthy plantation owners in the eastern part of the state, but received virtually nothing in return for their tax dollars.[i] North Carolina’s bankrupt post-Revolution “government” provided very little in the way of government for its western settlers—no significant development of roads, no schools, weak law enforcement, inadequate courts, and no protection from Indian incursions. By the time Abraham and Daniel settled in east Tennessee, many of the residents there were already clamoring for the kind of benefits state governments were expected to provide for their citizens. And it wasn’t long until clamoring turned into action, drastic action that led to a failed attempt for separate statehood.

[i] Foster, 2.

One minute video

State of Franklin

December 14, 1784 to March 1, 1788

On June 2, 1784, after several requests by the Continental Congress, North Carolina finally agreed to cede its western lands to the newly established United States and gave the Congress one year to accept the offer.[i] The proffer of cession was in a sense an “empty gift,” because of the “Land Grab” of October 20, 1783 through May 25, 1784.[ii] North Carolina had just “pocketed” revenue from the sale of four million acres of its most valued western lands and the offer to the United States by North Carolina required that previous land deals be allowed to remain valid.

[i] Robert E. Corlew, Tennessee: A Short History, Second Edition. (Knoxville, TN: The University of Tennessee Press, 1981), 73.

[ii] Atkins, 76.

When western Carolinians learned of the Cession Act, they were generally hopeful that the Continental Congress would provide the much needed help that North Carolina had failed to give. But they were temporarily left “without any form of government and with land offices closed” and “it was rumored that it might be two years before the federal government would accept the cession, leaving the area without protection and support from any government.”[i]

[i] Rae, 16.

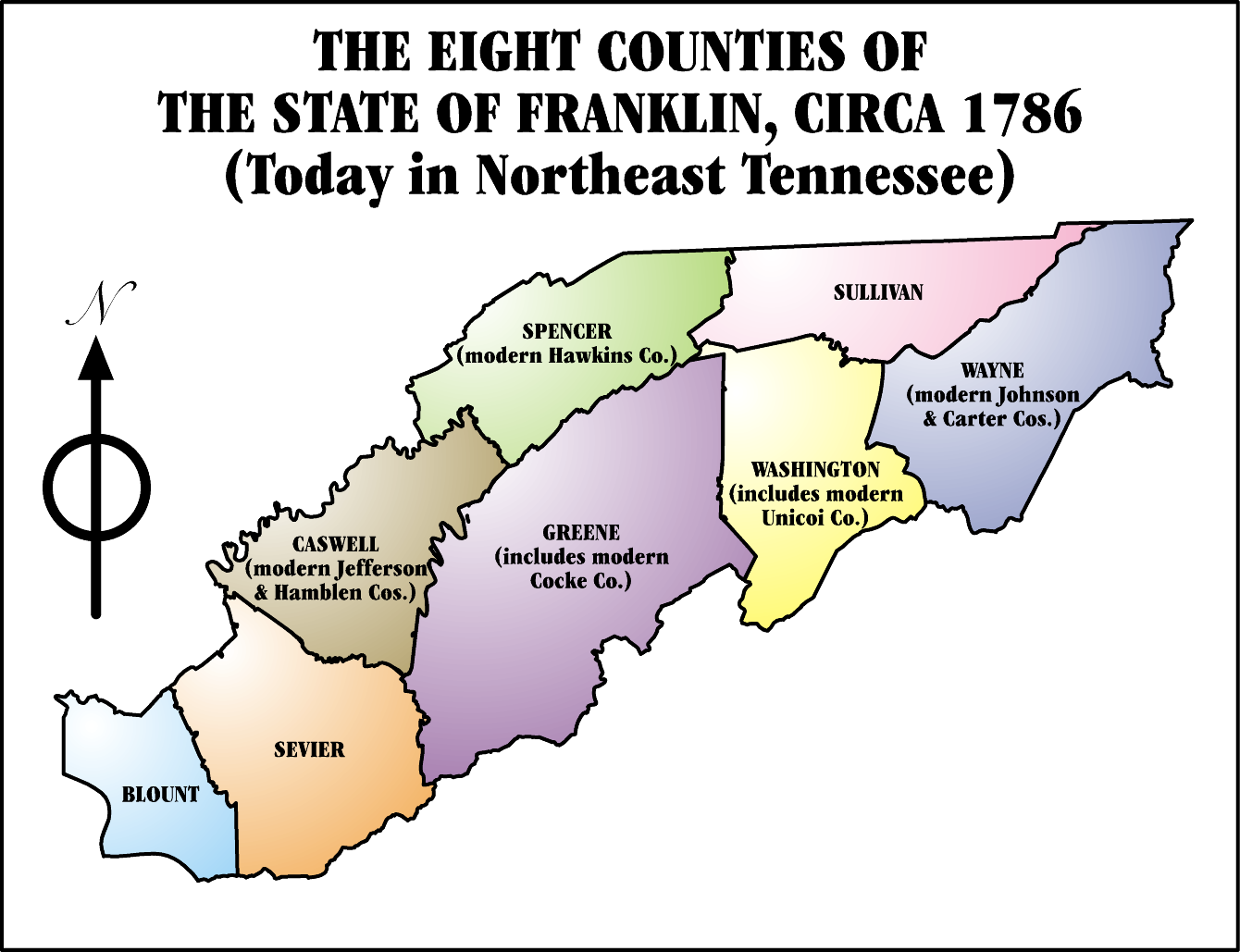

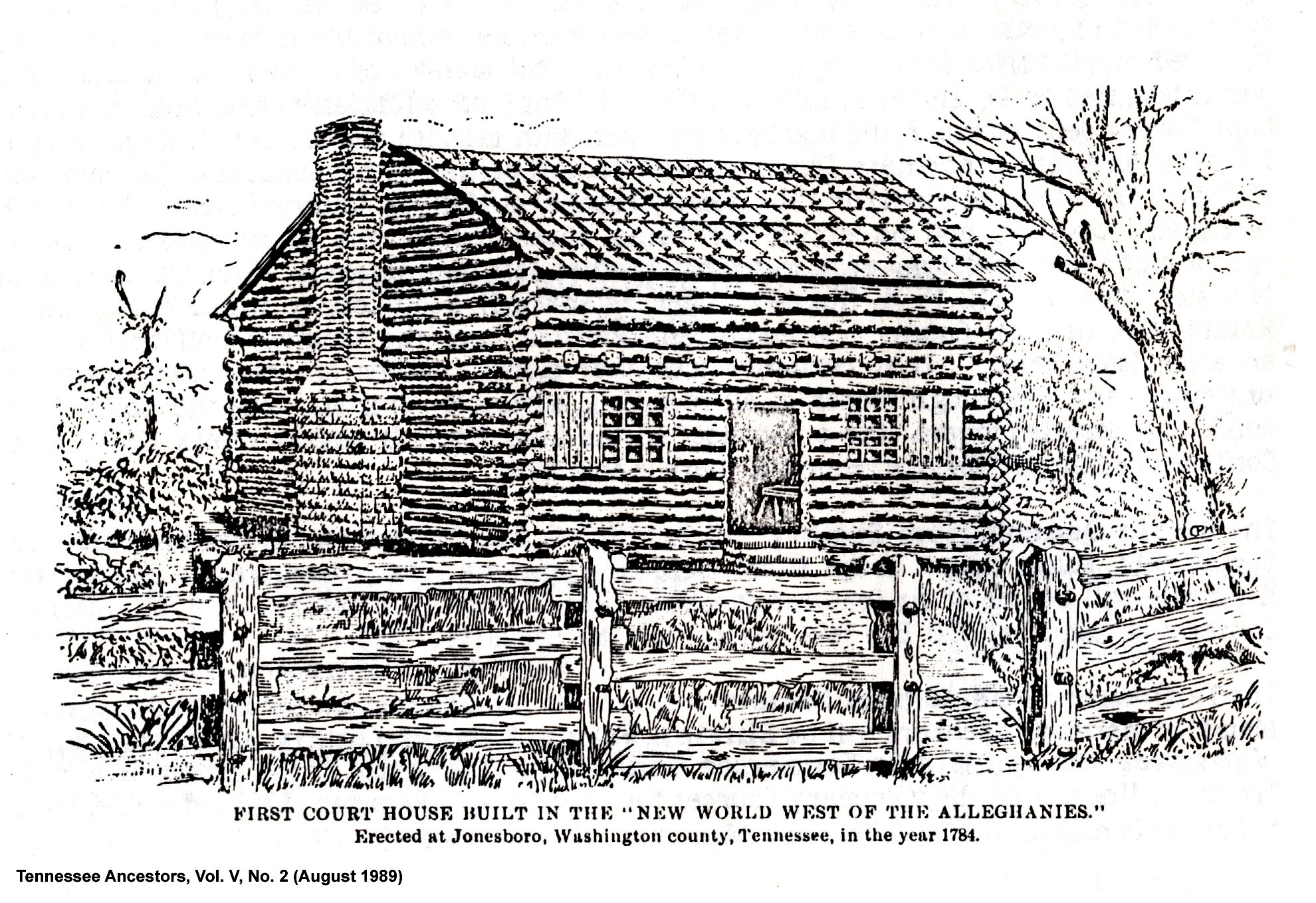

In quick response to the cession, on August 23, 1784 some prominent North Carolina citizens from Washington, Sullivan, and Greene counties (forty delegates in all) met at Jonesborough in Washington County to consider whether or not to create a new state, independent of their eastern mother state. But in November of that same year, just five months after the Cession Act (and two months after the Jonesborough meeting), North Carolina rescinded its offer before the United States Congress in Philadelphia could respond to the Cession Act.

North Carolina’s reversal did not put an end to the western leaders’ pursuit of a new state. The group met again in November, but that meeting broke up in confusion and a lack of consensus regarding the plan for a new government.[i] However, the leaders of the new-state movement met a third time in Jonesborough on December 14, 1784 and voted, 28 “yea” to 15 “nay,” to “form a new and distinct state independent of North Carolina.”[ii] “A member of the convention from the door of the rude courthouse announced the result to the large crowd that had been drawn to Jonesborough, and the proclamation was received with joyful acclaim.”[iii] There’s a strong possibility that Daniel Hiestand may have been in this crowd that assembled in the street of Jonesborough.

[i] Samuel Cole Williams, History of the Lost State of Franklin. (1924; second edition reprinted, Johnson City, TN: The Overmountain Press, 1993), 33.

[ii] Foster, 3.

[iii] Williams, History of the Lost State of Franklin, 41.

Two Shenandoah Valley, VA Men Take Opposing Leadership Positions

Two Shenandoah Valley transplants to eastern Tennessee took opposing positions in the decision and became bitter adversarial leaders throughout the next few years. Both of these men were from the general area of the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia where our Hiestand family lived! Colonel John Sevier had gained fame as an Indian fighter and key leader of the Overmountain Men who defeated the British and Tories on October 7, 1780 at the Battle of King’s Mountain. Sevier was born and grew up west of the Massanutten Mountain from the Henry Hiestand family and is credited with developing the town of New Market, Virginia before moving to the Carolinas. Sevier was a “yea” voter in the December Jonesborough meeting. Colonel John Tipton, a former Shenandoah County, Virginia militia leader, justice of the peace, sheriff, and member of the Virginia House of Delegates, voted “nay.”

In March 1785, the new state was officially organized and John Sevier was elected to be the state’s first governor. The initial choice of a name for the state was “Frankland,” meaning “Free Land.” But in an effort to gain the support of Benjamin Franklin, an American hero whom they hoped would help them become accepted into the United States, the state’s name morphed to “Franklin.” But Benjamin Franklin would have no part in supporting the proposed state. Four new counties were established within Franklin: Wayne, Spencer, Caswell, and Sevier. In August of 1785, the Franklin legislature chose the more centrally located town of Greeneville in Greene County as its capital, rather than Jonesborough. In response to the birth of Franklin, “John Tipton erected a powerful anti-statehood movement seeking to destroy the state of Franklin and elevate himself and his supporters into positions of political prominence.”[i]

[i] Barksdale, 60.

Daniel Heston's Vote for Pro-Franklin Candidates

On August 18, 1786, Daniel Heston voted for pro-Franklin candidates in an election conducted in Jonesborough on the third Friday and Saturday of August 1786. Daniel Haston’s vote at the Jonesborough polling site indicates that he was pro-Sevier and pro-Franklin, at least at the time of the August 1786 election. Anti-Franklin voters set up their polling place in a cave on John Tipton’s farm near Johnson City, TN. His brother, Abraham, apparently did not vote at either location.

Franklin’s leaders were unable to gain support for statehood from North Carolina, as well as the power brokers in Washington. So even though the Franklinites out-polled John Tipton and the Anti-Franklinites in the August 1786 election, their drive for United States statehood was not achieved at that time. But ALL of what had been Western Carolina would become the State of Tennessee ten years later, June 1, 1796.

Funny and Historically Informative Video

If you appreciated this article, please share it with others who might also enjoy it.