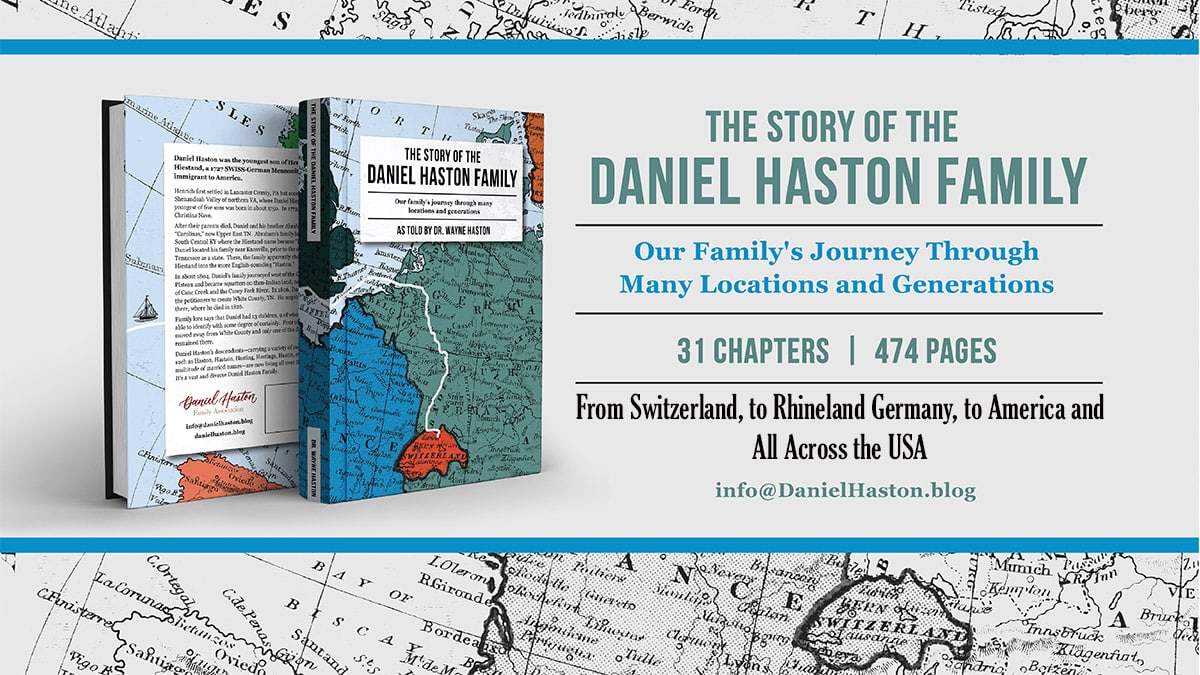

35 - David Haston - White County, Tennessee Pioneer, Part 2

David Haston, Esq. (Justice of the Peace)

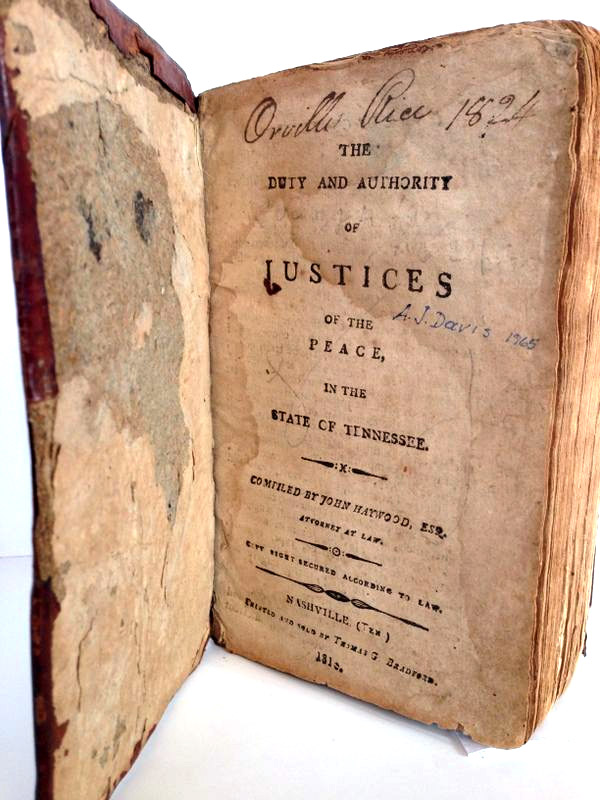

How did simple farmers and businessmen – many of whom had very little formal education – understand Tennessee (and county) laws enough to serve as county court judges? They were guided by a book like the one you see above. The first (1810) edition contained 372 pages.

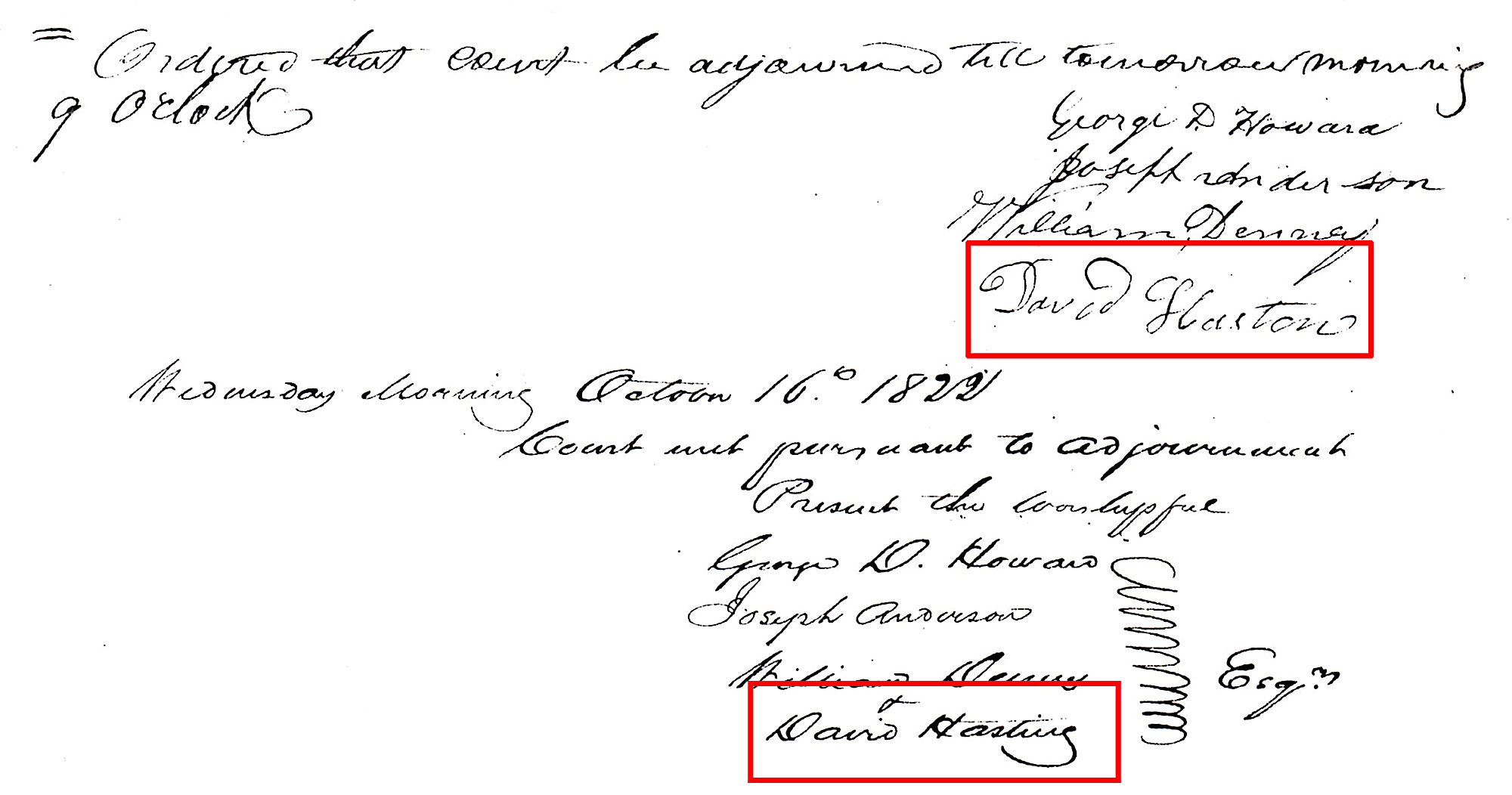

On October 14, 1822, David Haston was sworn in as a Justice of the Peace in White County and began to serve on the court the following day. He served in that role until sometime in 1836. In the mornings, the clerks recorded a list of the justices present (see the “Hasting” spelling), but when the justices closed out the session at the end of the day, they signed their names personally (see the “Haston” spelling in David’s own signature).

Roles and Authority of Justices of the Peace

The following description of the position and duties of justices of the peace in colonial Virginia[i] changed very little from that time and place to the first half of the 1800s in Tennessee. Going back to the colonial era, “justiceship of the peace was an honorable and dignified office. “Gentlemen” or “Esq.” was usually written after the name of justices, and the justices of a county were referred to collectively as “gentlemen justices.”

The official duties of the justice were two-fold. Individually he had minor powers and responsibilities which included settling suits for small debts; issuing peace bonds, and ordering persons to appear before the county court to answer an indictment. Collectively the justices of a county constituted the county court. It was in this capacity that the justices made their major contribution to local affairs and receive their major training in the art of government. In the colonial period and for many years thereafter, a man became a justice of the peace by qualifying under a commission issued by the governor.

The personnel of the bench changed from day to day and from session to session, sometimes by prior agreement, so that no one justice was unduly burdened and so that all had a share in the business of the court though naturally some were more active than others.* For performing acts of extraordinary importance…required that a majority of all justices be present.

*Justices conducted court by quorums. Tennessee law required three justices to be present for a quorum.[ii]

Court days were important occasions in the economy and society as well as in the government…. The business of the court brought men to the county seat; others came because the assemblage of farmers and planters made this a convenient time and place for transacting private business. These…gatherings gave welcome relief from the isolation and loneliness of country life.

Note: Justices of the Peace in Tennessee “were entitled to receive the sum of one dollar and fifty cents per day for every day they are [were] necessarily engaged in holding the courts, except the days set apart for county business.”[iii]

[i] Charles S. Sydnor, Gentlemen Freeholders: Political Practices in Washington’s Virginia. (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1952), 65, 84-85.

[ii] Haywood, Cobbs, Whiteside, and Chase, Volume 1, 199.

[iii] Haywood, Cobbs, Whiteside, and Chase, Volume 1, 199.

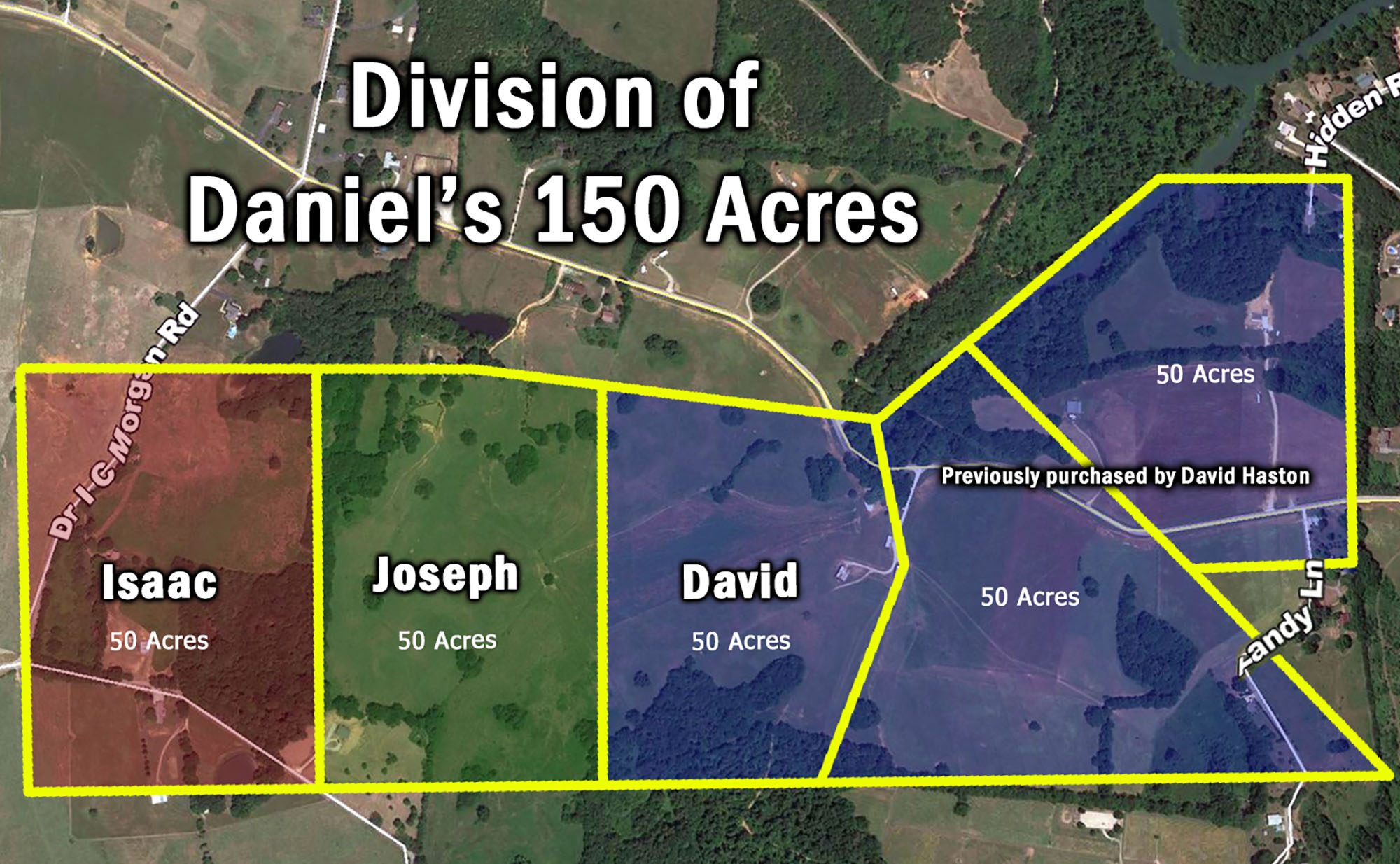

David Haston's Land Holdings

February 15, 1809

50 acres purchased from Joseph Haston (original grant # 550); adjacent to Daniel’s land on Big Spring Branch

January 16, 1812

50 acres purchased from Charles Mitchell; originally owned by Isham Bradley (grant # 529); adjacent to the 50 acres he purchased from Joseph Haston (grant # 550)

Before 1827

Apparently inherited 50 acres Daniel Haston home place when Daniel died; adjacent to David’s 100 acres |

February 5, 1827

Purchased 100 vacant acres for 1 cent per acre; Isaac Dodson, assignee; “on waters of Caney fork & on Cumberland Mtn.”

July 27, 1829

Purchased 71+ vacant acres for 1 cent per acre; adjacent to Shockley and Denney lands; appears to have been on mountain side

Maximum acreage in subsequent tax records = 295 Acres

David Haston, Politically an "Old Time Whig"

David’s son, William Carroll Haston, Sr., said that his father (politically) was an “Old Time Whig.” What does that mean? What did he stand for in politics?

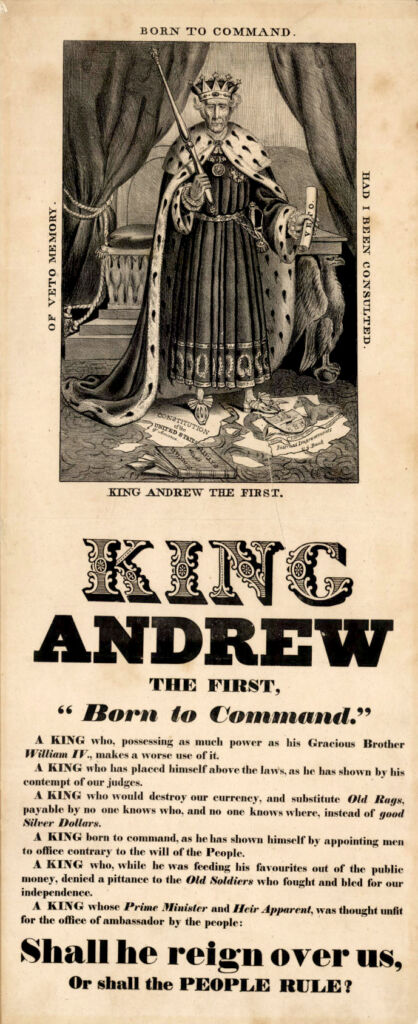

In the 1828 and 1832 presidential elections, 95% of Tennesseans voted for Andrew Jackson. But even some of Jackson’s staunchest Tennessee supporters and best friends became increasingly unhappy by some of his political views and decisions. And the more popular Jackson became, the less he seemed to be interested in being the populist “voice of the people”—the essence of his campaign platform. His opponents labeled him: “King Andrew the First.”

The term “Whig” was used in the American Revolution for Patriots, American supporters of the revolution.* Members of the anti-Jackson party cherished the name because of its historical significance and the similarities they saw occurring in their generation—the common people vs. King Andrew. Jackson gradually tended to ignore Supreme Court decisions and even the constitution when he found it to be in his best interest to do so.

*The name originated in England in the 1680s when Scottish Protestants resisted the threat of an establishment of Catholic Kings. A Presbyterian group there came to be called “Whigs,” short for “Whiggamores”—so-named because of the cry of “Whiggam” they used to prod their horses.

Even though Tennesseans tried hard to be loyal to their state’s hero, they came to be concerned about two of Andrew Jackson’s policies:

First, Jackson opposed a national banking system, with banks chartered by the Federal Government. Tennessee needed reliable banks for the financing of their agricultural enterprises. Later, when the Panic of 1837 and the depression that followed hit hard, the Whigs blamed Jackson and his successor, Martin Van Buren, for the financial disaster.

Second, Jackson opposed federal funds for “internal improvements”—roads, canals, railroads, etc. Being an inland state, Tennesseans faced major challenges getting their products to major markets. Tennessee needed these internal improvements.

These, and a few other, Jacksonian policies flew in the face of Andrew Jackson’s home state. Even then, Tennesseans were reluctant to abandon their state’s hero. But when President Jackson sought to impose his will on the American people regarding who should succeed him in the 1836 presidential election, many Tennesseans had had enough and began to shift to the anti-Jackson Whig Party. With Hugh Lawson White,* a Tennessean Whig, running for President, the state voted decisively against Jackson’s anointed choice, Martin Van Buren. The vote wasn’t close: 57.92% for White, 42.08% for Van Buren.

*Hugh Lawson White, son of General James White of Knoxville, had been one of Jackson’s most trusted allies but distanced himself from Jackson as the President overextended the constitutional powers of his office. Also, remember that Hugh Lawson White was the attorney hired by Samuel Cowan to prosecute Joseph Haston in the “timothy lot” case. White lost that case!

The Whig Party of the northern states differed somewhat from the Southern Whigs. But the issue of slavery was not a major issue with the Whigs, even though there were more abolitionists in the Whig Party than the Democrat Party. When the Whig Party dissolved in mid-1850s, anti-slavery Whigs found the newly formed Republican Party as their home. Most of the pro-slavery Whigs reunited with the Democrats.

Since David Haston died in 1860, prior to the Civil War, it is impossible to know his personal stance on slavery as a political issue, except for the fact that neither he (nor any of the other Haston men in White or Van Buren County, TN) ever owned slaves even though neighboring families were slave owners. For the Hastons in Tennessee, their participation in the Confederacy was probably a “States Rights” issue. Daniel and David Haston’s grandsons and great-grandsons in Tennessee fought in the Confederate Army, but some who lived in other places fought for the Union.

If you appreciated this article, please share it with others who might also enjoy it.